|

|

|

|

|

The Felon's Fang

The Hunt Is On For A Buffalo Cop

Killer.

Following the Lightning Path of

Buffalo’s Green-Tooth Slayer By Captain GEORGE F. TOURJIE,

Buffalo New York Police Department

True Detective Magazine, November 1940, |

| By J.

HOWARD GARNISH |

Deborah Kufel - Typist |

|

The Winter of

1929-1930 was a tough one for Buffalo Police. Fighting gangs

of bootleggers, hijackers and rum-runners were making the

snowy

Niagara

frontier a crimson

battleground.

Narcotics

peddlers were stealthily pursuing their nefarious calling.

Lightning thrusts or armed robbers kept merchants cowed.

Federal agents

co-operated with the police in the war on liquor runners, dope

and vice. But the robberies were the police department’s own

problem-a headache shared by all of us from Commissioner

Austin J. Roche down to the patrolman pounding their beats,

and including me and my fellow-members of the auto squad |

|

|

|

|

|

| From

late in September until the first of February , forty-one

holdups had been reported in the city and only eight arrests

had been made.

The newspapers

clamored for action. We were even more anxious than they to

wipe the unsolved cases off our records. Every apparently

successful stickup, we knew, lent encouragement to scores of

young fellows who thought armed robbery an easy to make a

living. But as hard as we tried, the list of unsolved cases

grew longer.

Some of the robbers

worked in bands, others in pairs, but several operated alone.

The elusive

A&P bandit was one of these. Since the previous November

he had robbed managers of

East Side

grocery stores of

money mounting into the thousands of dollars.

Holdups in a few

stores belonging to other chains were attributed to him, but

branches of the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company

appeared to be his favorites. Our records accused him of ten

of these jobs in about the same number of weeks. |

|

|

|

|

His

procedure was well patterned. Early Monday morning, before the

Saturday receipts had been banked, he would enter a store when

no customers were present, whip out a revolver, force the

manager, and clerk if one were present, to reveal where the

store’s cash was hidden, and truss his victims up in the

rear room with clothesline from the store’s stocks.

Hastily stuffing his haul into his pockets, he would dash

to a car parked near by and speed away. His visits were brief

but effective. By the time the police arrived he had vanished

like a phantom.

Store managers told

our detectives that the gunman was a slim, blond young man,

about five feet ten, with a scar on his lip and wearing

sideburns, a fashion that became popular among the

“sheiks” of that day in imitation of Rudolph Valentino.

And several

managers added-as the bandit curled his lip back to snarl his

commands, he bared a discolored front tooth of a greenish hue. |

|

Captain George F. Tourjie Buffalo Police

Department |

| The

detectives poured over record cards of known robbers in an

endeavor to find the one with a greenish tooth and a scarred

lip. They found nobody answering that description. They

summoned store managers to Headquarters to examine pictures of

likely suspects. Looking at the rogues gallery of photographs,

the managers shook their heads.

Studying the

detectives reports of the chain store stickups, Commissioner

Roche and Night Chief William R. Connolly looked for

information on the man’s operations. Finally the

Commissioner smashed a fist on his desk. |

|

|

|

|

“it’s

useless to chase this fellow!” he exclaimed. “we’ve got

to trap him! Most of his jobs have been pulled on Monday

mornings, so from now on our men are going to be waiting for

him.

A patrolman will

be stationed every Monday morning in each A&P store in the

vicinity in which he has been operating. The patrolmen will

have to work overtime, but these robberies must me stopped”

The baited traps

were set, but after a month the bandit still had eluded

capture. Perhaps he got |

| wind of the preparations for his

reception, for he suddenly changed his operating methods.

He

robbed a couple of stores outside the guarded district, then

shifted his forays from Monday mornings to Saturday nights,

just before closing time. He was still making big hauls and a

good portion of the force continued to lose sleep waiting for

him.

When Commissioner

Roche heard that he had been outmaneuvered, he became

thoughtful. “It’s tough to put extra loads on the

patrolmen” he told Chief Connolly, “but we’ve got to get

this man.

Have a policeman

assigned to each store for an hour before closing time every

Saturday and continue the morning details. If he keeps, he’s

got to walk into the trap sooner or later.” |

|

|

|

|

Commissioner

Austin J. Roche

|

Patrolman

Carl L. Wunderlich was one of the men called upon for extra

duty as part of the elaborate snare. Thus it was that , after

pounding his beat through the snowy night

and the gray dawn

of

February 3rd,

1930

he rapped sharply on

the door of the A&P store at

646 Sycamore Street

, near

Sherman

.

Joseph S. Braun,

twenty-two, of

118 Lemon Street

, acting manager of

the branch during the illness of his father, emerged from the

back room carrying a basket of vegetables to place on the

display. Heeding the knock, he deposited his load on the floor

and stepped to the door.

Patrolman

Wunderlich entered, stamping snow from his feet.

“Hope you’ve

got a good fire, Joe,” the policeman remarked. “This is

blue Monday and I’m just about blue from the cold. The

temperature’s been dropping since

midnight

.”

“I got the stove roaring as soon as I came to open up,”

Braun responded. “It’s fairly warm in the back room

now.” |

| “Doggone

you’re A&P bandit,” groused Wunderlich. “If it

weren’t for him I could be on my way home by now.”

“Well, if he shows up you better be ready for him,” Braun

countered. “We had a lively Saturday night trade and I’ve

got quite a stack of money hidden in back waiting for the bank

to open.”

Patrolman Wundelich stood for a moment longer inside the

door, watching Braun and his assistant, Harold R. Chapin,

twenty-three, arranging displays.

To

the right of the entrance a growing accumulation of trays and

baskets contained fruits and vegetables. To the left stood the

long grocery counter, the cash register at the wall behind it.

At the rear of the store, forming an L with the grocery

counter, was the shorter butter and cheese counter.

The

patrolman’s gaze turned to the partition that separated the

store from the rear room.

“Say,

when are you going to move those bags of potatoes from that

wall and bore a peephole there for me? He asked.

Young

Braun was apologetic.

“I

don’t like to take that responsibility, Carl,” he

responded. “Maybe, when Dad gets back…”

“I

might as well be home in bed as guarding this place,” the

policeman remarked ruefully. “I’d have to stand in the

doorway back there to know what’s going

on out here. Well, I’m going back by the stove.”

He

stalked to the entrance to the rear room, which was placed

midway of the partition, just beyond the end of the butter

counter and about on a line with the front door.

Turning

as he passed through the doorway, he skirted a masking

partition which hid the rear room from the curious eyes of

customers.

In

a little while Chapin came back an sat down a short distance

from the patrolman to work on the store’s books. |

|

|

|

|

Shortly

after

eight o’clock

, Braun was crouched

in the front window, taking an inventory of special sale

merchandise. A blond young man entered, his hands in his

pockets and his coat collar turned high against the cold and

snow.

Descending

from the window, Braun stepped behind the counter and asked

politely: “what will you have?”

|

|

For answer, the man

snatched his right hand from his overcoat pocket and leveled a

nickel-plated revolver at the white-aproned figure of the

manager.

“Get

to the back!” he ordered softly.

Braun

stared apprehensively at the man’s ruthless face, which

showed a scar slitting the thin lips. He regarded the weapon

in the bandit’s hand and wondered if Wunderlich and Chapin

had heard.

“What

do you want?” he asked as loudly as he dared, but his voice

shook uncertainly.

The

gunman leaned forward menacingly and merely gestured again

toward the rear room.

Braun

dared not shout, for fear of being shot. He could only hope

that Wunderlich had been warned and standing behind the

masking partition, his revolver cocked and ready.

The robber’s gun followed the manager as he

edged along the grocery counter, turned behind the butter

counter and reached the doorway.

It was shoved into his ribs as he backed through and

followed the masking partition.

As the pair approached the end of the shorter

partition, the gunman’s face twisted into a snarl.

Braun, facing him, caught a glimpse of a greenish

tooth. “Get the

stuff!” the bandit ordered. Hearing

the command, Chapin slipped into an alcove, out of sight. |

|

|

|

|

|

| In the same instant,

Braun saw the bandit’s alert eyes sweep the room and catch

sight of the policeman.

The manager was shoved aside.

A shot split the air. The

gunman turned and fled.

Regaining his balance, Braun dashed through the opening in

the partition, dove behind the counter and listened for

Wunderlich’s revolver to reply.

After a second’s wait, he called to the patrolman:

“Don’t shoot! The

holdup man’s gone.

”Just then Wunderlich staggered through the doorway into

the front of the store, his gun in his hand.

Blood streamed down his face.

As he came abreast of the butter counter, he collapsed

to the floor and began to moan.

Chapin dashed to his side. |

|

|

|

|

Braun ran outside and confronted a neighbor.

“Call Police Headquarters and get an ambulance” he

shouted. “A policeman

has been shot!”

The shrill screech of an ambulance siren mingled with the

scream |

|

of police cars as the vehicles drew up to the store.

Detective Sergeant John J. Whalen and his homicide squad

cleared a path through curious onlookers for the ambulance

crew. Kneeling beside

the prostrate blue-coated figure, the ambulance surgeon made a

quick examination.

“Shot through the right side of the face,” he murmured

to Detectives Walter A. Holz and John J. Fitzgerald.

“It looks as though it had pierced his jaw and

neck.” The surgeon

shook his head doubtfully.

He helped to lift the wounded patrolman on a

stretcher and the ambulance sped him to

Memorial

Hospital

.

While Carl Wunderlich fought for his life, the

entire might of the police force was whirled into action to

hunt down the criminal who had to shoot him before he’d had

a chance to draw.

Commissioner Roche ordered all policemen,

including day and night shifts, to work a seven-day week and

recalled immediately all men on leaves of absence.

He issued a call for volunteers for raiding

parties that night. More

than 100 patrolmen and detectives, who had already done their

normal tour of duty that day responded. |

|

|

|

|

A detective with the auto squad, I was

assigned to a day trick that week, but I joined the raiders.

The Commissioner was very earnest when we

assembled at Headquarters for instructions.

“Men”, he said solemnly, “you know

that last Saturday night two young bandits killed Adam Lampke

in his butcher shop in

East North Street

when he resisted them. Today

the A&P bandit has shot a patrolman-the very symbol of law

and order-and this officer will probably die.

These shootings must stop.

|

| “The homicide squad has a line on some

suspects, but we can’t rest with that.

I want you to go out and bring in for investigation

every suspicious character you can find.

Grab any one with a police record.

Be on your guard for any of these men may be a killer.

Don’t shoot unless you have to, but if you shoot,

don’t miss. All

right, get going!

The

dragnet that night swept in 400 men.

Some of them had been on our “wanted” list for

months.

For three days the cells at Headquarters and in the

precinct stations bulged with prisoners.

Several were booked on serious charges and eventually

convicted. But most of

them, after questioning and a checkup of their activities,

were released or received suspended sentences as leased or

received suspended sentences as vagrants.

A few meager clues about the A&P bandit proved

worthless.

Patrolman Wunderlich died the next afternoon, leaving a young

widow and a baby daughter, Audrey.

He had been married only two years.

We were all grimly determined that if the chance came the

bandit would pay dearly for his wanton killing.

Grimmest of all was Carl’s brother, Detective Henry

F. Wunderlich, one of my fellow-members of the auto squad.

Taking his dead brother’s service revolver, he swore

he would hunt down the killer.

All of us pledged our help.

Detective Sergeant Whalen and his homicide squad had been

busy piecing together fragments of information.

The store manager and his assistant gave descriptions

of the killer. Braun

mentioned the gunman’s sideburns and greenish tooth.

Charles Kelley, of 479 Sherman Street, had been walking

near his home the morning of the shooting, he told Detectives

Holz and Fitzgerald, when he saw a man dash around the corner

from Sycamore Street, leap into a black coupe parked in

Sherman Street about 100 feet from the corner and sped north.

The man wore a light-colored cap and a light overcoat

that came down below his knees.

The manager of the A&P branch at

440 Genesee Street

came forward with another morsel of information.

On the morning that Carl Wunderlich was wounded, he

reported, a young man, heavily built, about five feet ten

inches tall, wearing a light overcoat and light cap and a

white shirt without a collar, tried the door before the store

was opened.

The manager stepped to the front window and saw the man

walk to a car parked nearby, get in, and drive away.

He gave police the license number.

They learned the automobile had been stolen the

previous night from the janitor of a factory in the

neighborhood. It was

located soon afterward, abandoned.

Detectives theorized that the bandit, failing to gain

entrance to the

Genesee Street

store, had driven a few blocks to the

Sycamore Street

grocery where he had encountered and slain Wunderlich.

Detective Chief Emanuel Schuh showed the investigators’

reports to the Commissioner Roche, who studied them closely.

“I’ll have to turn the auto squad loose on this

fellow!” he exclaimed. He

summoned Lieutenant Arthur D. Britt, our squad leader.

“This killing,” the Commissioner told him, “will

probably compel the gunman to lie low for a while.

We know definitely now that he uses stolen cars for his

jobs. Sooner or later

he’ll steal another one. It

looks like a task for your man to nail him.

Get a line on his identity and track him down.”

In those days, before the advent of two-way police radios,

members of our squad saw plenty of action.

Our stolen car list regularly contained thirty to

thirty-five and even forty entries.

Today it will rarely exceed five.

While some of the car thieves were merely joy riders who

used the machines until the gas supply dwindled, more of them,

we knew, were hard-boiled gunmen with nervous trigger fingers.

The auto squad had been chosen to match the daring and

shooting prowess of the desperadoes it was likely to

encounter. Nearly every

member was a veteran of at least one gun battle with

criminals.

We knew the gunmen’s technique well.

They would steal a car, pull a robbery, and then

quickly abandon the machine. Another

favorite device was for thugs to step up to an amorous couple

in a parked auto, force them at gunpoint to surrender the

wheel, dump them out in a lonesome spot in the country, far

from a telephone, then use the car in a robbery before police

had learned it was stolen.

When Britt relayed the Commissioner’s orders, we nodded

grimly. “Be careful

with your guns,” our leader added.

“Don’t shoot heedlessly, but be on your guard every

instant. Remember this

criminal has killed one of the best shots in the department.

He’d just as soon kill another.”

We sallied forth, armed, to the teeth, but soon found that

the Commissioner’s surmise was correct.

Weeks went by and no new A&P stickups were

reported. We concluded

that the gunman was lying low, waiting until the “heat”

was off.

Meanwhile, the homicide squad and other officers in the

department ran down some hot leads.

What appeared to be the hottest came from Charles A.

Braden, a dispatcher for the Greyhound Bus Company at its

terminal at Court and Pearl Streets.

“About ten-thirty p.m. on the day Wunderlich was shot,”

Braden told Desk Lieutenant Walter E. Jackson, “a man about

thirty years-old, wearing a red and black lumber jacket, came

into the terminal and asked for a taxi.

None was there, so he called the Van Dyke Taxi Company

and asked to have one sent over.

The taxi dispatcher evidently asked him his name, for

he answered, “What difference does it make?”

Then he gave a name I didn’t understand.

I was reading an early edition of the morning paper as he

waited. He came up to

me and asked whether the policeman died who was shot at the

A&P grocery. He

became very nervous and pulled quite a sum of money out of his

pocket and counted it several times.

He hid in the corner as I walked to the top of the stairs.

He asked me if the taxi was in sight.

I told him I saw one coming.

He came as far as the door, then looked in both

directions before going out. As

the taxi drove away, “I took its license number.”

Police contacted the cab driver, Leavit Wilcox,

103 Maple Street

. He told where he had

taken his fare and added: When

I arrived there, he did not get out immediately.

He paid me while in the cab, and then I noticed a woman

come to a window and look out.

He then got out of the cab and ran to the side door of

the house. The woman

seemed nervous. “I

saw her go to the rear of the house, as if to let him in.” |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A squad of detectives

sped to the address given by Wilcox.

The man was arrested, brought in and persons who had

seen the killer viewed him. But

they said he was not the man.

Inspections of the rogue’s gallery by murder witnesses

turned up another hopeful lead.

After they had selected a picture, which they said,

“looked like” that of the slayer, investigation disclosed

that the man had left

Buffalo

the day of the shooting. A

devious trail led police to

Toledo

,

Ohio

, where he was picked up, waived extradition and was returned

to

Buffalo

. But when store

employees viewed him in the “show-up,” they shook their

heads again.

It was one of the many false leads.

But Night Chief Connolly was confident he had a more

hopeful one when about two weeks after the Wunderlich slaying,

he trapped a youthful desperado named Dombkiewicz into

spilling a tip about an acquaintance.

Petey Dombkiewicz; his sweetheart, Sally Joyce Richards,

and a third member of the “Gold Band Gang” had just been

returned to

Buffalo

after their capture in

Montgomery

,

Alabama

. Sally later pleaded

with the judge, who sentenced them both to Auburn Prison for

robbery, that she be permitted to marry Petey.

Knowing that the diminutive Dombkiewicz had lived near the

scene of the A&P stickup slaying and was widely acquainted

in the underworld, Connolly had him brought to his office,

ostensibly for a casual conversation.

The Night Chief led the conversation around to the A&P

holdups. Petey seemed willing to talk.

“That guy’s using hot cars,” Petey asserted,

apparently enjoying his role of oracle for the police.

“Some of them he snatches from parking lots and some

from the streets.”

Connolly had dug out fifteen or twenty pictures of chaps

who answered the description of Wunderlich’s slayer.

Several of them wore sideburns and some had defective

teeth, but police didn’t have anything definite against

them.

The pictures lay on Connolly’s desk as the pair talked.

It was a shot in the dark, but he picked up the

pictures and started going over them with Petey to watch his

reaction.

The prisoner had looked at several of them and the Night

Chief had about given up hope.

The officer showed him another.

Petey gave Connolly a hasty glance, started to say

something, then stopped in confusion.

“Know him, Petey?” Connolly

asked, but the prisoner saw he had given himself away and

clammed up.

As soon as he had been led back to his cell, Connolly

re-examined the picture that had caused Petey’s confusion.

It showed a rather good-looking, blonde young man who

wore his hair long on his cheeks in sideburns.

His name was Walter Krajewski. |

|

|

|

|

|

| The Night Chief was

elated, but puzzled too. Krajewski

was a pretty bad man, but hardly the type to be tagged as a

ruthless robber and killer.

From notations on the card Connolly determined that

Krajewski was then a little less than twenty-two years old.

Seven years before, he had been arrested for larceny

and juvenile delinquency and had received a year’s

probation. At sixteen

he had been nabbed in a dice game and fined five dollars.

A year later he was arrested on a petit larceny charge,

but the card didn’t show the disposition of the case.

At eighteen he had been arrested for burglary and

received an indefinite

term in Elmira Reformatory.

Then an interesting notation caught Connolly’s eye.

He called for the reports on the A&P stickups and

found that the first of the series had taken place on

November 25th, 1929

.

Checking back on

Krajewski’s record, the Night Chief learned that the suspect

had been released from the reformatory just a short while

before that date.

Quickly the word went out:

“Pick up Walter Krajewski. He’s

wanted for questioning about the murder of Patrolman Carl

Wunderlich.”

Armed with pictures of the

suspect, members of the homicide squad scoured the city, but

to no avail. After

prying around hi old hangouts, they got hold of an address.

They went there only to learn that Krajewski had moved

out a short time before without leaving a forwarding address.

The Headquarters men were

frankly stumped about where to look next.

It seemed to them that if their suspect were to be

found, he would have to be caught on the fly.

That was the status of the

case when I reported for my usual trick of duty with the

auto-squad on the chilly night of March 22nd.

It was a Saturday and Saturdays more than any other

nights meant trouble for our squad.

That was the night when merchants’ cash registers, as

well as the motion picture houses, were full, and the two

circumstances worked hand in hand for the benefit of the

gunmen.

The curbs of every block in

the downtown theater district were lined solid with parked

cars, and in the vicinity of every neighborhood movie house

were scores more.

It was a simple matter for

bandits to find a car that had been parked with the ignition

key in it, or to pick the lock or to wire around the ignition.

If they grabbed a car soon after it had been parked in

the theater district, they could be pretty sure of having two

and a half to three and a half

hours-until the show was over-to use the machine for

their own purposes before it was reported stolen.

Meanwhile, the robbery

reports would trickle in. If

a witness managed to catch a glimpse of the auto license,

invariably it belonged

to a stolen car, which would be found abandoned soon

afterward.

Lieutenant Britt and the

rest of our squad had been keeping a close watch on the

reports of recovered autos, to see what they could tell us.

The way we figured it, a holdup man or a pair of them

would abandon a car within a half-mile of their homes, so they

wouldn’t have far to walk. When

our checkup of the records showed that the overwhelming number

of stolen cars were recovered within a one-mile radius on the

East Side

, we figured that most of the gunmen lived in that area.

The Lieutenant’s

assignments were mad with that evidence in mind.

On that March night, six cars filled with auto squad

members were sent out roving on the

East Side

.

We wore plainclothes and our

cars carried no police signs. Only

the siren, if we were obliged to use it, revealed us as

policemen.

A few flakes of snow fell as

we drove about leisurely, our eyes fixed on the license plates

of cars that approached or passed ours, ready to check a

number against the list of stolen cars that dangled from our

dashboard. Whenever we

were in the vicinity of a precinct station, one of us stopped

“hot” cars to add to our list and checked with

Headquarters.

That night we had a big old

touring car with side curtains.

I was at the wheel and our squad leader, Detective

Louis M. Klein, rode at my right.

“Keep your guns handy, boys” he reminded us more

than once. “Remember

one of these guys may be the Wunderlich killer. |

|

|

|

|

Ordinarily Detectives

Fred Rambuss and Guy C. Dewey would have been with us, but

because of absences of other squad members due to illness and

days off that pair was assigned to another car.

In their stead Detectives John W. Crotty and |

|

John

Hamrahan were occupying the rear seat of our big Packard.

Crotty, whom we had nicknamed

“Two-gun,” carried his usual arsenal of two service

revolvers. Hanrahan had

a shotgun ready for instant service.

Klein and I each had a Police Positive in shoulder

holsters.

In the course of our prowling, we stopped

at the twelfth precinct station on

Genesee Street

to check in.

Klein emerged from the station and

reached for the stolen car list.

He added a license number and explained, for our

benefit, that it was a Chevrolet touring car reported at

10:57 pm

as stolen from Broadway and

Ellicott Street

in the theater district. The

owner was William Kunz of

337 Germain Street

|

|

|

|

|

We resumed our

cruising. After

traversing several streets in the heart of

Buffalo

’s Polish-American

center, we swung out

Walden Avenue

for a few blocks. As we

neared the trolley barns, a touring car with a winter top

approached us, climbing the grade from a railroad underpass.

By the beam of our headlights I caught the last four

numbers of its license.

“Get the first numbers of that Chevy.”

I flung over my shoulder at the detectives in the back

seat. “It’s a hot

car.” I repeated the

numbers I had caught to Klein and almost simultaneously Crotty

gave him the first numbers. “Yes,

that’s the last one on our list,” Klein confirmed.

“We’d better give him a looking over.”

|

| Already I was swinging the big Packard into the track area

in front of the trolley barns for a quick turn around.

Apparently

the driver of the stolen car became apprehensive, for he

quickly put on speed and swung sharply left into

Lathrop Street

, which we had passed

only a moment before.

Headed about, I shoved my foot on the accelerator and we

thundered in pursuit. The

car swayed dizzily as we swerved into

Lathrop Street

and saw the Chevrolet already half a block away.

Once under way on a straight stretch, the Packard was

swift. Slowly we began

to close the gap. But

busy

Sycamore Street

was the first intersecting thoroughfare and we were forced to

unleash the siren to warn other traffic away as we hurtled at

more than fifty miles an hour across the intersection.

Our hopes for a quick and

quiet pickup were destroyed as thoroughly as our screaming

siren shattered the peace of the neighborhood.

Halfway down the next block

the Chevy appeared to slow up as it swerved toward the curb.

Evidently the driver thought to leap from the stolen

machine and dash away on foot, but we were gaining too

rapidly.

Changing his mind, the

fugitive pressed on the pedal and the light car leaped ahead.

He hardly cut his speed as he approached crowded Broadway,

yanked the wheel into a right turn and a short block farther

turned right again, doubling back on us.

Close behind as we neared

Broadway, we soon lost our advantage.

The big gain we made on the straightaway was lost on

turns and in traffic, where the smaller car could be

maneuvered more readily.

Picking up speed again, we

zigzagged in pursuit, turned west into

Sycamore Street

and sped on. We had

nearly closed the gap again as we approached

Mills Street

with siren shrieking.

The fugitive driver, already

aware that he had an advantage on every turn, whirled toward

the intersection at full tilt, made a quick right angle and

fled northward. Our

heavy car screamed in anguish as I tried to duplicate his

quick turn and an echoing yell came from the back seat.

“Heh, you trying to kill us? Shrilled one of our

detectives recovering his equilibrium after being hurtled

against his companion.

Klein had his revolver out,

ready for action, and mine hung loose in my holster, but we

dared not shoot, for we didn’t know whom we were chasing.

Our elusive quarry might be a high school boy who had

swiped a car for a joyride, in which case wee would be

severely criticized if we were to kill or wound him.

On the other hand, if he

were a desperate gunman we would be just as severely

criticized if he got away, and there was a very good chance

that he might, if some unwary motorist were to get mixed up in

the pursuit.

At the next cross street the

Chevy swung right then sped for eighteen blocks on a

meandering route that nearly duplicated the earlier stage of

the chase. It brought

us to

Genesee Street

, where we tore along between two lines of traffic.

The stolen car dipped into

the railroad underpass and swerved right again into the next

intersecting street with our curtained juggernaut less than

100 yards behind. |

|

|

|

|

We were slowing down

slightly to make the turn when a shot shattered the center of

our windshield. A

vacant lot on the corner had given the fugitive a chance to

fire out of the right side of his car into ours without

slackening speed.

“Anybody hurt? I yelled at

Crotty and Hanrahan in the back.

“No, it missed us” they returned.

It was a miracle none of us was hit for as we

determined later the bullet had passed directly between Klein

and me and had continued through the back curtain.

|

|

“Okay, let him have it,”

Klein gritted. “He

asked for it.”

Another shot splattered

against our radiator. Klein

pushed his revolver through the opening of the side curtain

and fired.

We had no doubt now of the

kind of customer with whom we were dealing, but we still

weren’t certain that the driver was alone in the Chevrolet.

We only knew that at any cost, we must overhaul him,

forcing him to the curb if possible.

He must not get away.

A spray of glass showered us as another shot struck our

windshield. Klein

pulled out a big piece of loose glass and Hanrahan, standing

up in the rear, leveled his shotgun through the opening and

fired a blast. Crotty’s

and Klein’s Police Positives spoke sharply.

It was impossible to know what mark their shots had found

for the Packard was swaying down straightaways and careening

around corners, flinging my passengers from side to side and

upsetting their aim.

No longer were we losing so much distance on the turns.

I was driving out in the center of the streets, ready

for a turn either way and taking them with hardly a letup in

speed barely missing the far curb on each one.

The fugitive resumed his grim game of twisting, turning,

ducking in and out of traffic, in a desperate effort to shake

off our relentless pursuit.

Every few minutes we would catch a flash in the car ahead

and a “ping” would resound on our machine.

My companions would fire an answering salvo whenever it

was safe. He didn’t

care whom he killed, but we had to be cautious so we

wouldn’t hit an innocent bystander. |

|

|

|

|

Through a maze of streets the chase led

again to

Sycamore Street

, a main East-West artery.

|

| A woman screamed and fled from the street

to the sanctuary

of the sidewalk as the two machines took the turn on two

wheels.

A revolver spoke and out of the tail of my eye I saw a man

duck into the protection of a doorway.

A quick turn and we wheeled north, around the block and

back toward sycamore.

Into that busy thoroughfare we plunged, to come as close to

sudden death as any of us has ever known.

Sycamore is one of the liveliest streets on the East side

and its intersection with

Fillmore Avenue

is near the center of the section’s business district, which

is jammed with shoppers and merrymakers on a Saturday night.

As we approached

Fillmore Avenue

, the signal light turned red but the Chevy plunged ahead,

getting the jump on the cross-traffic.

Even so a car quick on the pickup sprang from the waiting

line of cross-traffic and whirled across the intersection

barely missing the rear of the stolen machine.

Tearing along close behind at sixty to seventy miles an

hour, with siren screaming, we couldn’t have stopped if we

had wanted to. It

appeared certain that we would plow into the car that was

cutting across our bow.

I swung the wheel hard to the left; the Packard shivered in

every brace and beam. It

almost seemed to me that I could smell hot metal as the other

car slithered past. I

still am not sure whether we scraped it, but I never want to

come closer. |

|

|

|

| Past the intersection,

we quickly gathered speed again.

My companions in the back seat were silent, trying to

keep right side up in the thundering chariot as they took aim

between the ears of Klein and me in front and fired at the

elusive target ahead.

Avoiding the rough cobblestones of

Sycamore Street

, both autos swung into the trolley tracks.

We were by then only two car lengths behind.

My fellow detectives had ceased firing.

“They must have emptied their guns.”

I thought, “and they can’t reload with the car

swaying like this.” |

|

| Out of my

shoulder holster I snatched my own revolver.

Smashing out a piece of glass, a remaining fragment of

the Packard’s windshield, with the butt, I rested the gun

barrel on the metal frame and fired-one, two, three, four

shots.

The Chevy continued straight ahead.

I decided I must save one shot for our protection when we

overhauled our quarry. “I’ve

got to make this next one good,” I resolved.

I took careful aim and fired.

The Chevy continued on its course.

“Hang on, I’m going to belt him!” I yelled at my

companions, bringing the Packard’s speed down to the

Chevy’s so we would escape serious injury in the collision.

We had just passed

Walnut Street

when I pressed a bit more on the accelerator and our heavy

machine plowed into the light car ahead.

It jumped out of the car tracks and veered to the

right. For half a block

it edged toward the side of the street, hurdled the curb,

plunged straight into a fire hydrant and an adjoining power

pole. The pole snapped

near its base. The

Chevy came to a halt-after a five-and-three-quarter-mile

chase.

A sudden swerve to the left and a quick

cutback, as a car approached from the opposite direction and

the Packard was brought under control.

A geyser of water gushed from the smashed hydrant as I

pulled up ahead of the battered car that we had pursued for

sixty-nine city blocks.

We pile out.

With revolver leveled and only one shot remaining in

it, I approached the stolen machine.

Then I returned my pistol to its holster.

Before me, lying with his head hanging out of the open

door on the driver’s side and his body slumped behind the

wheel was the gunman. He

must have been dead before our car rammed his. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Klein, Crotty, and Hanrahan lifted him

out and carried him across the street, where they laid him on

the snow-covered ground.

I waded through the freezing water,

fishing for his weapon. After

a few minutes I found it-a nearly new Colt .38.

Opening the gunman’s coat, we found he was wearing a

new shoulder holster and he had a box of cartridges in a

pocket.

Meanwhile, Police Headquarters had been

deluged with reports of a gun battle on the

East Side

. It was only a few

minutes before

|

|

Commissioner Roche and Night Chief Connolly

arrived with a squad of Headquarters men.

Connolly glanced at the body on the

ground, then fished in his pocket brought out a picture and

made comparisons.

“This is Walter Krajewski-the fellow who killed Carl

Wunderlich,” the Night Chief declared.

“And we’re just lucky he didn’t kill us, too,”

I commented.

An hour later Connolly’s identification

was proved correct. Summoned

from their beds, Acting Manager Braun of the A&P store and

Kelly, the man who saw

Wunderlich’s slayer flee from the store, picked our

victim’s body from five others in the morgue.

At Braun’s request, an attendant

flipped back the dead man’s lip.

There was the greenish-hued tooth that Braun said was

so prominent when the A&P bandit, his lip writhing,

snarled his commands at the chain store manager nearly seven

weeks before.

Fingerprints proved that the dead man was

Krajewski.

The Medical Examiner found a bullet hole

in Krajewski’s head, evidently made by the last shot I had

fired.

A short while later, the four of us who

participated in the pursuit and killing of Patrolman

Wunderlich’s slayer received checks for $250 each, equal

shares of the reward posted by the Great Atlantic &

Pacific Tea Company.

Detective Henry Wunderlich, who was

detailed to another auto squad patrol that night, was well

satisfied with the outcome of the case.

“I didn’t want any part of the

reward,” he told me. “I

just wanted to get the rat who killed my brother.

I’m glad you nailed him.”

The back of the stolen car had been

peppered with twenty-nine shots.

Our own big vehicle was ready for the junk heap, its

bullet-riddled radiator dry and the motor ruined.

But it had served well in bringing to an end the sordid

career of a young man who had graduated from petty crime to

banditry and thought he could get away with murder. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note

Lieutenant George F. Tourjie former

Sergeant of Marines was presented with the William J. Conners

gold medal on

December 18th, 1980

for the most meritorious act performed by a

Buffalo

police officer during the year.

He was elected by the three

Buffalo

police inspectors, Thomas J. Gilligan, James Hyland and John

S. Marnon, comprising the award committee, to receive the

medal for his work on the case about which he tells in the

foregoing article.

As Fred M. McLennan, managing editor

of the Courier-Express, pinned the medal on Tourjie’s

breast, he said:

“The smashing blows struck against

murderous thieves last March brought to an abrupt end a

gangster outbreak that boded ill for the peace and good name

of the city. We are all

inclined to be hero worshippers.

We are apt, however, to turn back the pages of history

and pay homage to

heroes whose deeds are no more meritorious than those that

occur before our eyes. In

the warfare against gangsters the members of the

Buffalo

police force have demonstrated that they are of the right

caliber to form that thin blue line that stands between the

law-abiding citizen and the felon.

George F. Tourjie, recipient of the medal this year is

an outstanding example of the brave, efficient police officer.

Detectives John Hanrahan and John W.

Crotty were awarded departmental medals for meritorious

service in connection with the same case. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note Crime Scene Photo Not Authentic

|

|

|

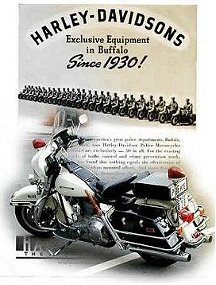

OFFICERS

MEMORIAL

POLICE VEHICLES

POLICE BADGES

AMUSEMENT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

LINKS

IN

THE NEWS

1800's

1910's

1920's

1930's

1940's

1950's

|

1960's

1970's

1980's

1990's

2000's

2010's

|

POLICE OFFICERS

Chief Executives

On the Job

Police Officers

History of Police Woman

History of Black Officers

Meet Detective Sergeant Coyle

Meet Detective Sergeant Burns

Meet Patrolman Nicholas Donahue

Buffalo Housing 1980's

Precinct 16

Days Gone By

POLICE SQUADS

Underwater Recovery Team

Homicide Cold Case Squad

CSI Crime Scene Investigation

S.W.A.T.

Mobile Response Unit

K-9 Corps

Communications Division

Motorcycle Squad

Mounted Division

Band and Drill Team

Cartography Unit

Pawnshop Squad

Printing Department

Identification Bureau

HISTORY

History Overview

Police Precincts

Mutual Aid

World War II

Desert Storm

CRIME STORIES

Detectives 1980

The Blue Ribbon Gang

The Mystery Perfume Case

The Felons Fang

Contract For A Hit

An Eye For Murder

The Boarder Bandits

Detective William Burns

MOB

STORIES

Callea Brothers Murders

Magaddino Cheats Death

Aquino Brothers Murders

DeLuca Gangland Murder

Battaglia Gunned Down

Gerass Found In Trunk

Cannarozzo Shooting

Albert Agueci Murder

Birth Of Witness Protection

Murder Gangland Style

How America Meets The Mob

Anti-Gambling Crusader Murder

The Easy Money

|