|

Federal

Narcotics Case Court

of Appeals

United

States Court of Appeals

310

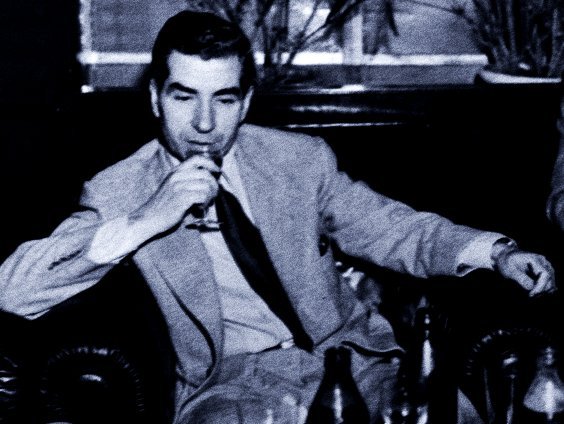

F.2d 817: United States of America, Appellee. v. Vito Agueci,

Filippo Cottone, Robert Guippone, Luigi Lo Bue, Matthew

Palmieri, Anthony Porcelli, Charles Shiffman, Rocco

Scopellitti, Charles Tandler and Joseph Valachi,

Defendants-appellants

United

States Court of Appeals Second Circuit. - 310 F.2d 817

Argued

October 4, 1962 Decided November 8, 1962

Jerome

Lewis, New York City (Theodore Krieger, New York City, on the

brief), for Filippo Cottone, appellant.

Lawrence

A. Kobrin, New York City, for Rocco Scopellitti, appellant.

Menahem

Stim, New York City, for Joseph Valachi, appellant.

Frances

Kahn, New York City, for Luigi Lo Bue, appellant.

Albert

J. Krieger, New York City, for Charles Shiffman and Charles

Tandler, appellants.

Theodore

Krieger, New York City, for Robert Guippone, Anthony Porcelli

and Matthew Palmieri, appellants.

T.

F. Gilroy Daly, Asst. U. S. Atty., Southern District of New

York, New York City (Vincent L. Broderick, U. S. Atty.,

Sheldon H. Elsen, Arnold N. Enker, Michael F. Armstrong, Peter

K. Leisure, Asst. U. S. Attys., on the brief), for appellee.

Before

LUMBARD, Chief Judge, and FRIENDLY and KAUFMAN, Circuit

Judges.

KAUFMAN,

Circuit Judge.

1

The

ten defendants before us appeal their convictions for

violation of the federal narcotics laws, 21 U.S.C. §§ 173,

174. The defendants were sentenced to imprisonment for periods

ranging from five years to twenty-five years,1

after a two-month trial before a jury in the Southern District

of New York. The indictment, filed on May 22, 1961, contained

thirty counts. The first count charged all of the appellants

and several others with conspiracy to violate the narcotics

laws, commencing in September 1958 and continuing until May

1961; counts two through thirty separately charged various

defendants with substantive violations. Several individuals

were named in the indictment as coconspirators but not as

defendants2

and other coconspirators named as defendants were not tried

below for various reasons.3

Michael Maiello was also convicted but died while his appeal

was pending.

2

At

the trial, the Government's case depended principally upon the

testimony of two witnesses, Salvatore Rinaldo and Matteo

Palmeri, who had not been named as defendants in the

indictment but had been charged with participation in the

conspiracy. Their testimony was offered to establish that the

appellants and numerous other persons had engaged in a single

conspiracy to import from Italy large quantities of heroin,

which they adulterated, packaged, distributed, and sold in the

United States. The conspiracy, defined generally, involved the

importation of narcotics into this country by concealed

packages hidden in valises or false-bottom trunks, most of

which were unwittingly brought to New York piers by Italian

immigrants. These immigrants were requested to bring the

trunks and valises to this country by a travel agent in Italy,

purportedly as a favor to some friends here. Whenever this

method proved for some reason unsatisfactory, one of the

appellants would travel abroad in order personally to assure

the success of the venture. For convenience, we may refer to

the small body of coconspirators who initated the various

importations and the subsequent distributions and sales of the

narcotics as the "executive group." The Government's

witnesses established that the members of this group were

Albert Agueci,4

Frank Caruso, Vincent Mauro, and John Papalia, none of whom

are appellants, and Vito Agueci, Luigi Lo Bue, and Joseph

Valachi, appellants here. In addition to these men, appellant

Rocco Scopellitti was also implicated in the importation

scheme, for he was alleged to have personally imported heroin

into this country in August 1960.

3

Upon

ascertaining the precise dates of the arrival in New York of

the narcotics being imported, one of the members of the

executive group would contact Matteo Palmeri, the Government

witness, who ran a bakery in Brooklyn.5

Palmeri, using his bakery truck, would drive to Pier 84 in

Manhattan, seek out the immigrant who was bringing the trunk

or valise containing the narcotics and identify himself as a

friend of the Italian travel agent, and return with the trunk

or valise to his bakery. On one occasion, when Palmeri's truck

was out of order, he enlisted the aid of appellant Filippo

Cottone. Palmeri was often assisted by Salvatore Rinaldo, the

other chief witness for the Government. Rinaldo would perform

a test on the white powder contained in the hidden packages to

assure that it was heroin. The packages of narcotics were at

first hidden in Palmeri's bakery, and later in Rinaldo's home

in Mount Vernon.

4

Until

October 21, 1960, when they were arrested, Palmeri and Rinaldo

were the primary distributing agents for the conspiracy. They

would be contacted by one of the members of the executive

group and instructed to deliver a specified quantity of

narcotics to a specified individual at a specified time. Thus,

in the month of July 1959, Caruso told Rinaldo to meet with

appellant Matthew Palmieri in order to consummate a sale. In

December 1959, Valachi introduced appellant Anthony Porcelli

to Rinaldo for a like purpose, and in April 1960, Porcelli

introduced Rinaldo to another appellant, Ralph Guippone. The

three coconspirators — Rinaldo, Porcelli, and

Guippone — would adulterate the heroin in Rinaldo's

home, sell the product to other individuals named in the

indictment but not here on appeal, and share in the proceeds

of the sale. In May of 1960, at a racetrack rendezvous, and at

the instructions of Caruso, Rinaldo met with appellant Charles

Shiffman who was later instrumental in arranging sales of

narcotics from Rinaldo to appellant Charles Tandler.

5

This,

in skeleton outline, is the manner in which the alleged

conspiracy operated and the manner in which each of the

appellants was implicated. This information will be helpful in

giving form to the narrative of specific events, which

follows.

6

The

indictment charges a continuing conspiracy from September 1958

until the date of its filing, May 22, 1961. The testimony of

Government witnesses Palmeri and Rinaldo establishes the

sequence of events through October 21, 1960, when both were

arrested. In October of 1958, Matteo Palmeri met Albert Agueci,

one of the members of the executive group, in Brooklyn; in

response to questioning Palmeri indicated that he would be

interested in participating in a plan to smuggle diamonds. The

following month, appellant Luigi LoBue appeared at Palmeri's

bakery in Brooklyn, and he informed Palmeri that he was aware

of his interest in diamond smuggling, which information had

been conveyed by Albert Agueci. In May of 1959, LoBue again

contacted Palmeri, telling him to go to Pier 84 in order to

pick up a valise from a named passenger and to identify

himself (Palmeri) as a friend of Salvatore Valenti, the

Italian travel agent who was allegedly responsible for

"planting" the valises with Italian immigrants.

Palmeri did so and delivered the valise into LoBue's hands at

the bakery. Some days later, LoBue returned to the bakery with

five packages which he gave to Palmeri to be hidden. Soon

after, Palmeri brought those packages, on LoBue's

instructions, to Vincent Mauro, who, along with LoBue, is

alleged to have been a member of the executive group. Mauro,

over the course of a few days, paid $15,000. to Palmeri, who

in turn passed the money on to LoBue; Palmeri was rewarded for

his efforts with $300.

7

In

July 1959, LoBue told Palmeri that he had received a letter

from Italy and that Palmeri should report to the pier and meet

the passenger named in the letter, procure the valise, and

return to the bakery. Palmeri did so, and upon observing LoBue

remove a blanket from the valise, cut it open and withdraw

packages of white powder, Palmeri was told by LoBue that they

were dealing not in diamonds but in narcotics. Again, Palmeri

was requested to hide the packages, and he again made another

sale at Mauro's direction, receiving $15,000. That month,

Palmeri was introduced to Salvator Rinaldo, the other chief

Government witness, and from that time Palmeri delivered

heroin to Rinaldo, in order to facilitate the latter's sales.

The first such sale was from Rinaldo to defendant Matthew

Palmieri, in exchange for $8500., which money Rinaldo

transmitted to Caruso. This incident occurred in July 1959.

Another sale on precisely the same terms was carried out

between Rinaldo and appellant Palmieri on March 21, 1960.

8

Rinaldo's

position as central distributor became even more secure when,

in December 1959, Mauro, of the executive group, told

appellant Valachi, another member of that group, that

narcotics were to be picked up from Rinaldo. Valachi met with

Rinaldo that month, and introduced him to appellant Anthony

Porcelli; Valachi said that Porcelli was working for him and

that it would be Porcelli who would pick up narcotics from

Rinaldo in the future. The next morning, with Valachi standing

nearby, Rinaldo delivered a package of heroin to Porcelli,

which was paid for over the course of two or three weeks.

Rinaldo turned over the proceeds of the sale to Caruso. In

January of 1960, Rinaldo was introduced to two additional

contacts6

to whom further sales were made.

9

In

late January, LoBue notified Palmeri, the baker, that a third

shipment of narcotics was arriving in a valise carried by a

named Italian immigrant on March 7, 1960. Palmeri performed

his usual function, retrieved the valise with the hidden

packages of narcotics, and passed these on to Rinaldo, who

tested a sample of the substance from each of the packages. He

found it to be heroin. Soon thereafter, on March 19, Rinaldo

met with appellant Valachi, who informed him that "he was

going away", and that in his absence, Rinaldo should deal

with appellant Porcelli and with one Michael Maiello. Valachi

said that although he was going away, Porcelli and Maiello

would be taking care of him and sharing with him any profits

these two would make on the sale of narcotics. It turned out

that Valachi was indeed "going away" soon, for nine

days later he surrendered to federal authorities on another

charge and was incarcerated in prison.

10

Losing

little time, Porcelli went to Rinaldo's home in Mount Vernon,

in April 1960, and introduced appellant Robert Guippone; he

said that Guippone was one of the men who was carrying on in

Valachi's interest while Valachi was imprisoned. Plans were

made to dilute quantities of heroin with milk sugar, to sell

them, and share the profits. The dilution and sales were made

on several occasions in the months of May, June, August, and

September 1960, and Rinaldo, Porcelli, and Guippone shared in

the handsome profits, with some of the money going, on at

least one occasion, to Caruso. These transactions represent

the eleven substantive counts on which both Porcelli and

Guippone were convicted.

11

At

approximately the same time that Guippone and Porcelli first

met with Rinaldo in April 1960, a meeting of several members

of the executive group took place at a Manhattan restaurant.

They there decided that future narcotic importations would be

in trunks with false bottoms rather than in valises. That

month, appellant Vito Agueci went to Italy, for what he

claimed was a visit to his aged parents. The Government, of

course, places a different interpretation on the facts and

points out that this was not the only purpose to be reasonably

inferred from this trip, for proof was introduced that in May

of that year, Vito Agueci wrote a letter from Italy to Palmeri,

telling him that a trunk and a valise would be brought into

this country on June 2, 1960, and that Palmeri should be there

to pick them up. Rinaldo accompanied Palmeri to the pier at

that time; he later tested the packages secreted in the trunk

and valise and found them to contain heroin, weighing fifteen

kilograms.

12

Notification

of the next shipment came quickly upon the heels of the June 2

importation. In July, Palmeri received a letter from Salvatore

Valenti, the Italian "travel agent", informing him

that appellant Rocco Scopellitti was to arrive from Italy on

August 10. On that morning, Palmeri was contacted by Albert

Agueci, appellant's brother and member of the executive group,

who told him that Scopellitti worked for him and was to be

fully trusted. At the pier, Scopellitti and Palmeri loaded the

trunk into Palmeri's truck and drove back to the bakery. En

route, Palmeri asked Scopellitti when he was returning to

Italy and Scopellitti replied that he would go whenever Albert

Agueci wanted him to pick up another trunk. When they reached

the bakery, they were greeted by Rinaldo, who had earlier been

instructed by two members of the executive group that he was

no longer to acccompany Palmeri to Pier 84 but was to wait for

him at the bakery. Palmeri introduced Scopellitti, telling

Rinaldo that Scopellitti was "all right", and that

he had made the trip from Italy with the trunk; Scopellitti,

to dispel any further doubt, said "Don't worry. I know

what it's all about." The three proceeded to rip open the

false bottom of the trunk which revealed packages of heroin.7

Rinaldo took the packages to his home; he tested them and

found them to contain heroin.

13

While

these two shipments of June and August 1960 were being planned

and consummated, Rinaldo was making further sales at the

behest of the executive group. In late May, Caruso told him to

meet with appellant Charles Shiffman at the Roosevelt Raceway,

which Rinaldo did. A night or two later, Rinaldo was

introduced to appellant Charles Tandler. It was there agreed

that Shiffman would transmit certain code phone calls to

Rinaldo, whereupon Rinaldo would meet with Tandler at an

appointed rendezvous for the purpose of selling him narcotics.

Pursuant to this plan, Rinaldo delivered three kilograms of

heroin to Tandler shortly after this meeting at the racetrack.

Three kilograms were again delivered to Tandler on August 13

and four more in early October. On October 10, Shiffman and an

associate paid Rinaldo $25,200 for the last sale to Tandler,

and Rinaldo turned the money over to Caruso.

14

The

fifth shipment of narcotics was again preceded by a letter

from Italy, informing Palmeri that a trunk would arrive on

September 2. Palmeri drove to Pier 84 but was unable to claim

the trunk because he could not find the immigrant who had

shepherded it from Italy. After some frantic phone calls and

some impatient days of waiting, it was finally learned that

the claim check and the keys to the trunk could be found at a

given address in Garfield, New Jersey. Palmeri procured the

check and the keys, and was prepared to set out for the pier

when he found that his truck was not in working order. Albert

Agueci previously had informed Palmeri that in case of such

difficulties he should contact Filippo Cottone, one of the

appellants. Palmeri did so and told Cottone that he needed his

help to get down to the pier to pick up a trunk containing

narcotics; he promised Cottone $300 for his services. En route

from the pier back to the bakery, Cottone was critical of

Palmeri and his associates for the mishandling of the pickup

of the trunk. "I can't understand * * * how you people do

things, it is ridiculous"; he added that there had been

no trouble with the other shipments. At the bakery, where

Rinaldo was again waiting, Cottone was introduced by Palmeri,

who endorsed him as being "all right". The three

ripped open the trunk's false bottom, which contained ten

packages of heroin. Cottone took away one of the blankets in

which three kilograms of heroin were concealed but which

Palmeri had overlooked; these were soon retrieved by Palmeri.

Rinaldo again tested samples and found heroin.

15

Vito

Agueci, during the month of September 1960, took a second trip

to Italy. From there, he notified Palmeri that another

shipment was due October 21st, and Palmeri in turn notified

Rinaldo. Rinaldo relayed the message to Porcelli in a

conversation with him in Mount Vernon. Shortly before the

narcotics were to arrive, Caruso of the executive group

informed Rinaldo that the woman who ran Palmeri's bakery was

growing suspicious; all future imported trunks were therefore

to be taken directly from the pier to Rinaldo's house. Palmeri

was informed of the new routine, and on October 21 both he and

Rinaldo went to Pier 84 and picked up what was to be the last

shipment of narcotics. It was en route to Rinaldo's home in

Mount Vernon that both men were arrested by Westchester County

police and federal narcotics agents. The trunk they were

transporting was found to contain ten kilograms of what was

determined by United States Government chemists to be heroin.

16

We

shall first consider those contentions raised by the

appellants which affect all or several of them; we shall then

proceed to discuss those contentions specifically raised on

behalf of particular defendants.

17

THE

CONSPIRACY INSTRUCTION

18

The

appellants challenge the propriety of the trial court's

instructions regarding the scienter necessary to a finding of

conspiracy to violate the federal narcotics law, specifically,

21 U.S.C. § 174. Even assuming that defendants may be heard

to complain despite their failure to call the alleged error to

the judge's attention, see Screws v. United States, 325

U.S. 91, 107, 65 S.Ct. 1031, 89 L.Ed. 1495 (1945);

United States v. Atkinson, 297

U.S. 157, 160, 56 S.Ct. 391, 80 L.Ed. 555 (1936);

United States v. Massiah, 307

F.2d 62 (2d Cir., 1962), we hold that Judge

Herlands adequately covered in his charge all the elements

necessary to warrant a finding of guilt for participation in a

narcotics conspiracy. He charged as follows:

19

"Count

1 of the indictment charges that each of the defendants on

trial conspired to violate the Federal Narcotic Laws. In order

to convict under the first count of the indictment, you would

have to find:

20

"First:

that sometime between September 1, 1958 and May 22, 1961, in

the Southern District of New York, a conspiracy to violate the

narcotic laws existed between any one of the defendants on

trial and any other defendant, either on trial or not on

trial, or any co-conspirator named in the indictment.

21

"Second:

you would have to find that it was part of this conspiracy to

do any one of the following:

22

"a.

Unlawfully import and bring large amounts of narcotic drugs

into the United States from Italy; or "b. To receive,

conceal, buy, sell and facilitate the transportation,

concealment and sale of large amounts of narcotic drugs after

they had been imported and brought into the United States,

knowing that the said narcotic drugs had been brought into the

United States illegally; or

23

"c.

To dilute, mix and adulterate large quantities of the said

narcotic drugs prior to distribution.

24

"Third:

In addition to your finding that there was a conspiracy, and

that it was part of the conspiracy to do one of these three

things just enumerated, you would have to find that at least

one of the 14 overt acts charged in the indictment was

actually committed * * *.

25

"The

fourth and final element you would have to find as to each of

the defendants is that he knowingly became a member of the

conspiracy." (Emphasis added.)

26

This

instruction made it plain beyond challenge that the crime

charged was a conspiracy to violate the narcotics law and that

requisite to a finding of such violation is knowing

participation in a scheme having as an objective the

importation of narcotics contrary to law, or the knowing

transportation or facilitation of sales of narcotics after

they have been knowingly brought into the country illegally,

or the knowing adulteration of those very narcotics. It is

thus clear that United States v. Massiah, 307

F.2d 62 (1962), recently decided by this Court

(Chief Judge Lumbard dissenting) — even assuming

its correctness — is not in point. The fatal error

in the judge's instruction in Massiah was his failure "at

any point in his charge on the conspiracy count to

instruct the jury that knowledge of illegal importation was a

necessary element of the conspiracy" to violate the

narcotic laws. 307

F.2d 70. (Italics in the original). There the trial

judge devoted his instructions to those elements common to all

criminal conspiracies rather than focussing on the narcotics

aspect of the conspiracy; the latter would have required that

the jury find the defendants to have had knowledge that the

narcotics had been or were to be unlawfully imported.

27

Not

only did the trial judge in Massiah fail affirmatively to

instruct the jury on the element of knowledge, but it was

determined on appeal that certain passages in the court's

discussion of the general law of conspiracy actually

"suggested to the jury that knowledge of importation was

not necessary * * *" (307 F.2d at 70). The majority of

the Court cited this passage from the charge: "One may

become a member of a conspiracy without full knowledge of all

the details of the conspiracy or of all of the

conspirators." Appellants point to a similar passage in

Judge Herlands' charge, but even in that passage, there is an

important difference in emphasis. He stated: "It is not

necessary that one be fully informed as to the details of the

scope of the conspiracy in order to justify an inference of

knowledge on his part." (Emphasis added.) This

instruction pointedly emphasized the need to find that the

defendants charged with conspiracy had knowledge of the

general illicit purposes of importation, transportation, or

adulteration; it cautioned the jury that omniscience regarding

every aspect of the conspiracy was not indispensable to a

finding of such knowledge but that legitimate and reasonable

inferences of such knowledge could be drawn. This is an

unchallenged maxim of criminal law. We recently held in United

States v. Aviles, 274

F.2d 179, 188 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 362

U.S. 974, 80 S.Ct. 1057, 4 L.Ed.2d 1009 (1960),

that individuals who purchased narcotics from one of the

conspirators were themselves participants in the conspiracy if

"it is clear that they knew the nature of the operation.

Whether they knew its full extent and all of its activities

and actors is immaterial." See United States v. Rich, 262

F.2d 415, 418 (2d Cir., 1959).

28

Upon

a reading of the whole charge, see Carey v. United States, 111

U.S.App. D.C. 300, 296

F.2d 422, 426 (1961), Gilmore v. United States, 256

F.2d 565 (5th Cir., 1958), we are convinced that

the jury had constantly before it the judge's admonition that

the elements set down in 21 U.S.C. § 174, among them

knowledge of the illegal importation, were indispensable to a

finding of guilt on the conspiracy count.

29

EVIDENCE

OF A SINGLE OVERALL CONSPIRACY

30

Several

appellants contend that, although the indictment charged a

single continuing conspiracy from late in 1958 until the time

of the filing of the indictment, there was proof of several

separate and independent conspiracies. The variance in proof

is deemed by these appellants to be of such a serious and

prejudicial nature that reversal is required. See Kotteakos v.

United States, 328

U.S. 750, 66 S.Ct. 1239, 90 L.Ed. 1557 (1946);

United States v. Russano, 257

F.2d 712 (2d Cir., 1958). We find that there was

ample proof to warrant the finding of a single continuing

conspiracy.

31

The

Government's evidence successfully assimilates the conspiracy

before us to the model of the so-called "chain"

conspiracy, so familiar in other narcotic cases. See

Blumenthal v. United States, 332

U.S. 539, 68 S.Ct. 248, 92 L. Ed. 154 (1947);

United States v. Aviles, 274

F.2d 179 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 362

U.S. 974, 80 S.Ct. 1057, 4 L.Ed.2d 1009 (1960);

United States v. Stromberg, 268

F.2d 256 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 361

U.S. 863, 80 S.Ct. 119, 4 L.Ed.2d 102 (1959);

United States v. Rich, 262

F.2d 415 (2d Cir., 1959). The "chain"

conspiracy has as its ultimate purpose the placing of the

forbidden commodity into the hands of the ultimate purchaser.

See Note, "Federal Treatment of Multiple

Conspiracies," 57 Colum.L.Rev. 387, 390 (1957). That form

of conspiracy is dictated by a division of labor at the

various functional levels — exportation of the drug

from Europe and importation into the United States,

adulteration and packaging, distribution to reliable sellers,

and ultimately the sale to the narcotics user. Here the

members of the executive group — among them,

appellants Vito Agueci, Luigi LoBue, and Joseph Valachi

— formed the core of conspirators. They arranged

for the exportation of large quantities of narcotics from

Italy, for their importation into this country, and for their

safe delivery from the New York piers for ultimate

distribution by Palmeri into the hands of Rinaldo who would

arrange for sales in successive transactions. Scopellitti and

Cottone were participants, each on one occasion, in this

process. Rinaldo was shown to be the central distributor, the

key "link" in the "chain", and from him

the distribution and sale links — composed of

Porcelli, Guippone, Palmieri, Shiffman, and Tandler

— carried the narcotics to the ultimate purchaser.

32

Guippone

and Porcelli contend that the evidence against them reveals,

at best, a separate enterprise between them and Rinaldo,

devoted to the adulteration and sale of narcotics quite

independent of the conduct of the other members of the

conspiracy. The answer to this is that the mere fact that

certain members of the conspiracy deal recurrently with only

one or two others does not exclude a finding that they were

bound together in one conspiracy. Here, there was ample proof

that both Porcelli and Guippone were left to carry on the

interests of appellant Valachi while the latter was in prison.

Valachi had indeed introduced appellant Porcelli to Rinaldo

and stood nearby when a sale was consummated between the two.

Both Porcelli and Guippone had to be aware, by the nature of

the enterprise, that Rinaldo was constantly being supplied

with new quantities of narcotics; their repeated adulterations

of the narcotics over a period of several months, their

expressed intention to carry on the interests of Valachi, one

of the members of the executive group, their splitting of the

profits of their sales on at least one occasion with Caruso,

another member of the executive group, readily support that

conclusion. Knowing of these outside sources, it was enough to

make Porcelli and Guippone members of the overall conspiracy

that the success of their "independent" venture was

wholly dependent upon the success of the entire

"chain". United States v. Bruno, 105 F.2d 921 (2d

Cir.), rev'd on other grounds, 308

U.S. 287, 60 S.Ct. 198, 84 L.Ed. 257 (1939); see

United States v. Aviles, 274

F.2d at 188. An individual associating himself with

a "chain" conspiracy knows that it has a

"scope" and that for its success it requires an

organization wider than may be disclosed by his personal

participation. Merely because the Government in this case did

not show that each defendant knew each and every conspirator

and every step taken by them did not place the complaining

appellants outside the scope of the single conspiracy. Each

defendant might be found to have contributed to the success of

the overall conspiracy, notwithstanding that he operated on

only one level. See United States v. Stromberg, supra.

33

The

nature of the enterprise determines whether the inference of

knowledge of the existence of others in one overall conspiracy

is justified. It is clear that in a narcotic conspiracy case

of this nature no one member of the group can by himself

insure the success of the venture; he must know that combined

efforts are required. See United States v. Bruno, supra, 105

F.2d at 922. "[T]he conspirators at one end of the chain

knew that the unlawful business would not, and could not, stop

with their buyers; and those at the other end knew that it had

not begun with their sellers." In Bruno, narcotics were

smuggled into New York and ultimately sold in Texas and

Louisiana as well as in New York. Four groups were involved

— the smugglers, the middlemen, and two groups of

retailers. The importers could not profitably stay in business

without a selling outlet and the reverse was true, for the

retailers required a continuing source of supply. Comparison

of the facts in Bruno with those in the oft-cited case of

United States v. Peoni, 100 F.2d 401 (2d Cir., 1938), relied

on by appellants, shows the inappositeness of the latter. In

Bruno the evidence sufficed to warrant the jury's finding that

defendants knew remote links must have existed; in Peoni it

did not. Had the prosecution in Peoni been able to establish

more than one sale from Peoni to Regno, the inference that

Peoni knew that sales beyond his own would be made, and that

he thus shared a common purpose with Dorsey as Regno's vendee,

might well have been strong enough to warrant submission to

the jury. Kotteakos v. United States, 328

U.S. 750, 66 S.Ct. 1239, 90 L.Ed. 1557 (1946),

where the success of any individual illegal transaction was

independent of the success of any other, is sufficiently

distinguishable. Kotteakos is usually given as the prime

example of the so-called "circle" or

"wheel" conspiracy, which is not what we are dealing

with here. See Note, 57 Colum.L.Rev. 387, 388-389 (1957).

34

In

any event, the test for reversible error, if two conspiracies

have been established instead of one, is whether the variance

affects substantial rights. Fed.R.Crim.P. 52(a). The material

inquiry is not the existence but the prejudicial effect of the

variance. While we believe, as we have already stated, that

the jury could find there was but one conspiracy, the finding

of more than one conspiracy would not result in prejudice to

any of the defendants in the case before us. See Berger v.

United States, 295 U.S. 78, 82, 55 S.Ct. 629, 79 L.Ed. 1314 (1935). The

requirements for sustaining a verdict in which there has been

a variance have been met. The several conspiracies, if there

had been such, could have been joined in a single indictment

or consolidated for a single trial and the conduct of the

trial was such that the danger resulting from the admission of

evidence not chargeable to any appellant was minimal. See

Blumenthal v. United States, 332

U.S. 539, 559-560, 68 S.Ct. 248, 92 L.Ed. 154

(1947); Hanis v. United States, 246

F.2d 781, 789 (8th Cir., 1957); Ritter v. United

States, 230

F.2d 324, 328-329 (10th Cir., 1956); United States

v. Antonelli Fireworks Co., 155 F.2d 631, 635 (2d Cir.), cert.

denied, 329

U.S. 742, 67 S.Ct. 49, 91 L.Ed. 640 (1946); Note,

"Developments in the Law of Criminal Conspiracy," 72

Harv.L.Rev. 920, 992 (1959). Again Kotteakos, where the

prosecution of thirty-two defendants resulted in proof of at

least eight separate conspiracies, is inapplicable.

35

Appellant

Palmieri contends that there was insufficient evidence to

support his conviction on the conspiracy count. Since we find

that his conviction on substantive count 5 of the indictment,

for a sale of narcotics on March 21, 1960, was sufficiently

supported by the evidence, any discussion of his conspiracy

conviction is rendered moot; Judge Herlands imposed concurrent

sentences on each count. See Sinclair v. United States, 279

U.S. 263, 299, 49 S.Ct. 268, 73 L.Ed. 692 (1929);

United States v. Mont, 306

F.2d 412, 414 (2d Cir., 1962).

36

EVIDENCE

OF NARCOTICS IN THE SUBSTANTIVE COUNTS

37

It

is not necessary, in order for the Government to prove its

case of conspiracy to violate the narcotic laws, that there be

proof of actual dealings in narcotics. All that need be proved

is the unlawful agreement and an overt act committed in

pursuance of the agreement. The "conspiracy is a crime in

and of itself, separate and apart from the crime of

importation, purchase, sale, and transportation of

narcotics." Poliafico v. United States, 237

F.2d 97, 105 (6th Cir., 1956), cert. denied, 352

U.S. 1025, 77 S.Ct. 590, 1 L.Ed.2d 597 (1957). Cf.

Braverman v. United States, 317

U.S. 49, 54, 63 S.Ct. 99, 87 L.Ed. 23 (1942);

Pereira v. United States, 347

U.S. 1, 11, 74 S.Ct. 358, 98 L.Ed. 435 (1954). The

rule is otherwise, however, with regard to substantive

violations of the narcotics laws; there, the jury must be

convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the substance

imported sold, concealed, or adulterated was in fact a

narcotic drug. This element, under the terms of 21 U.S.C. §

174, is requisite to a conviction. But it is not necessary

that it be proved by direct evidence. Just as with any other

component of the crime, the existence of and dealing with

narcotics may be proved by circumstantial evidence; there need

be no sample placed before the jury, nor need there be

testimony by qualified chemists as long as the evidence

furnished ground for inferring that the material in question

was narcotics. See United States v. Morello, 250

F.2d 631, 633-634 (2d Cir., 1957).

38

The

appellants who have been convicted on substantive counts do

not challenge these principles of law. They contend, instead,

that the trial judge did not adequately compartmentalize the

circumstantial evidence as it was relevant to the proof of

narcotics in a particular substantive count charged against a

particular defendant. It is contended that the jury was, in

essence, instructed that in determining the guilt of one

defendant under a substantive count of the indictment, they

should weigh evidence relating to other substantive counts, to

other defendants, and to transactions in which the particular

defendant was not even involved. The judge's instruction is

therefore contended to violate the principle laid down in

United States v. Bufalino, 285

F.2d 408 (2d Cir., 1960), that proof in a mass

conspiracy trial must be individualized and compartmentalized,

defendant by defendant and count by count. Evidence admissible

to prove only the conspiracy was, it is argued, improperly

employed to prove the individual substantive counts.

39

We

hold that Judge Herlands' instructions on the use of

circumstantial evidence to determine that the material in

question was narcotics in the various substantive counts were

adequate. He charged that there were seven categories of

circumstantial evidence which the jury might consider in

determining whether a given defendant had possession of or had

imported the narcotic drug as charged in each substantive

count: (1) Rinaldo's testimony that he had personally tested

samples of the powder from each shipment; (2) the secrecy and

deviousness with which the transactions were handled (i. e.,

false-bottomed trunks, use of linings in the blankets, code

words, etc.); (3) the fact that the substance in which they

were dealing was a white powder; (4) the high prices paid in

cash for the substance; (5) the lack of complaint on the part

of the purchasers; (6) descriptive language used by certain of

the defendants in connection with certain transactions; (7)

the white powder in evidence which the United States chemist

testified was heroin hydrochloride. A conviction on similar

evidence was upheld in Toliver v. United States, 224

F.2d 742, 745 (9th Cir., 1955).

40

In

a trial of this dimension, each juror is faced with a

difficult task in compartmentalizing the evidence with regard

to each particular defendant and keeping clearly in mind the

full circumstances of each transaction. It is the function of

the judge, in his instructions to the jurors, to marshal the

evidence that they have seen and heard presented such that

justice may be meted out to the individual rather than to the

group. Our concept of criminal responsibility, like our

concept of moral responsibility, is rooted in the individual,

his intentions, his motives, and his conduct. The trial judge,

therefore, has the burden of impressing upon the jury the need

for judging each defendant separately upon each separate

substantive count charged in the indictment. We feel that

Judge Herlands patiently and capably performed this task. His

instructions to the jury were replete with admonitions that

"you must be convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that the

substance involved in each of such substantive counts was a

narcotic drug * * *."

41

That

portion of the charge on circumstantial evidence of narcotics

most likely to result in harmful side effects to the

defendants was the following: "6. The Government claims

that its witnesses, Palmeri and Rinaldo, testified as to

admissions by certain of the defendants that they were

dealing with narcotics in connection with certain

transactions." (Emphasis added.) Even there, the emphasis

upon particular defendants in particular transactions is

strong. We feel that any possible ambiguity was cured by the

passage almost immediately following: "If the evidence

convinces you beyond a reasonable doubt that the substance

involved in a particular count — and you must

consider the evidence count by count — was heroin,

you may conclude that this element of the offense charged in

the particular count has been proved. If, on the other hand,

the evidence does not convince you beyond a reasonable doubt

that the substance involved in a particular count was heroin,

you must find the defendant or defendants named in the

particular count not guilty on that particular count."8

Reading the charge in its entirety and observing the emphasis

which the trial judge placed on the necessary requirements of

proof, we cannot agree that the jury was not instructed on the

need to compartmentalize the evidence and on the consideration

it was to give to the evidence as it applied to each defendant

on each substantive count.

42

The

Government further argues that were we to construe Judge

Herlands' charge as suggested by the appellants, there was no

error, for anything said or done by a conspirator in

furtherance of the conspiracy is admissible against every

other conspirator, even on a substantive count. This principle

of law, they argue, is operative despite the absence of a

charge of conspiracy in the indictment. We are referred to

Pinkerton v. United States, 328

U.S. 640, 645-648, 66 S.Ct. 1180, 90 L.Ed. 1489

(1946), and United States v. Pugliese, 153 F.2d 497 (2d Cir.,

1945). The appellants reply that the application of principles

of agency to the criminal law, see 4 Wigmore, Evidence § 1079

(3d ed. 1940), has been restricted to cases of actual aiding

and abetting, to cases of present specific participation in

the specific acts which make up the crime charged in the

substantive offense; the principles are said not to extend to

cases of broad-ranging conspiracy. Since we have held that

Judge Herlands adequately compartmentalized the evidence with

regard to the substantive offenses of the individual

defendants, we are not required to determine whether each item

of evidence could not properly be considered against each

conspirator under the rule of law advanced by the Government.

43

Appellant's

final attack upon the proof that the material was narcotics

addresses itself to the sufficiency of the evidence on this

phase of the case. We reject this argument, for we find the

evidence introduced to establish that the material in question

in the substantive counts was narcotics to be quite

convincing. All the narcotics referred to in those counts went

through the hands of Rinaldo, who testified that he tested a

sample from each shipment, except the last, and found

narcotics each time. The last shipment, as well as samples

from some earlier shipments which Rinaldo had hidden in his

home, were tested by United States Government chemists and

found to be narcotics. The appellants contend that Rinaldo's

tests — change of color upon the addition of nitric

acid and liquification upon heating the powder to between 230°C

and 240°C — were insufficient to prove that the

substance was narcotics. They urge that other chemical tests

must be performed before the substance can definitively be

determined to be narcotics. But surely there was sufficient

evidence, albeit not conclusive to a mathematical certainty,

to warrant a reasonable inference to that effect. The

Government need not exclude every remote possibility of

innocence before its case warrants submission to the jury. See

Holland v. United States, 348

U.S. 121, 139-140, 75 S.Ct. 127, 99 L.Ed. 150

(1954); United States v. Tutino, 269 F. 2d 488, 490 (2d Cir.,

1959).

44

INSTRUCTIONS

ON DEFENDANT'S PRIVILEGE NOT TO TESTIFY

45

Appellant

Tandler did not take the stand during the course of the trial.

Judge Herlands, in summarizing the defense theories and

contentions offered on behalf of defendants Shiffman and

Tandler, instructed the jury as follows:

46

"Now

the defendant Shiffman took the stand. The defendant Tandler

did not take the stand. The fact that the defendant Tandler

did not take the stand does not give rise to any presumption

or inference against him or adverse to him. As you know, under

the Constitution, Fifth Amendment, no defendant in a criminal

case can be compelled to be a witness against himself; and

that means that in a criminal case a defendant has the

prerogative and privilege not to testify, and the fact that he

does not testify does not in any way, directly or indirectly,

permit you to draw any inference adverse to the defendant. A

defendant has the right to rely on his presumption of

innocence and to put the Government to its proof."

47

At

the conclusion of Judge Herlands' instructions, Tandler's

attorney excepted to the language in this passage referring to

the Fifth Amendment and to the privilege against

self-incrimination. It is argued by Tandler, and by appellants

Lo Bue, Palmeri, and Valachi, who also chose not to testify,

that a reference to the Fifth Amendment, in an era when it is

said resort to that amendment creates an indisputably

unfavorable inference, was prejudicial and constituted

reversible error. While most likely it would have been better

if the judge had not mentioned the Fifth Amendment, his

statement, in the context of the passage quoted above and also

of the supplemental charge he later gave in response to an

objection by Tandler's counsel, was not reversible error.

48

At

common law, the accused in an ordinary criminal prosecution

could not be called as a witness in his own behalf, because

under the rules governing litigation until the middle of the

last century, he was deemed "incompetent" to testify

at all. This incapacity pre-existed the drafting of the

Constitution and the Bill of Rights. The accused's incapacity

to testify in a federal court was removed in 1878 by what is

now Title 18 U.S.C. § 3481: "In trial of all persons

charged with the commission of offenses against the United

States * * * the person charged shall, at his own request, be

a competent witness. His failure to make such request shall

not create any presumption against him." It is therefore

usually assumed that the constitutional provision,

"though not at all necessary, when adopted, to guard the

accused against being called, were intended to preserve that

result of the incompetency from being abrogated by

legislation." McCormick, Evidence, § 122 at 257 (1954).

The outstanding authority on evidence likewise treats the

constitutional privilege against self-incrimination as the

modern-day foundation for the accused's privilege not to take

the stand. See 8 Wigmore, Evidence, §§ 2251 at 296, 2268 at

406 (McNaughton Rev.1961). We believe therefore that it was factually

proper for Judge Herlands to charge as he did regarding

defendant Tandler's failure to take the stand.

49

Appellant

Tandler has made an effort to distort the judge's instruction

into an "unfavorable comment", calling to our

attention several cases stating the rule that a conviction

should be reversed if the court comments unfavorably on the

failure of an accused to testify. Quercia v. United States, 289

U.S. 466, 471-472, 53 S.Ct. 698, 77 L.Ed. 1321

(1933); Allison v. United States, 160

U.S. 203, 209, 16 S.Ct. 252, 40 L.Ed. 395 (1895).

We find these cases completely inapposite. It is patently

contrived to argue that Judge Herlands was commenting

unfavorably when in the very same passage to which objection

is taken he charged twice that the jurors were forbidden to

draw any adverse inferences; he also explained that the

defendant has a right to rely on his presumption of innocence

and to put the Government to its proof. In so doing, Judge

Herlands' charge could be construed as even more favorable to

Tandler than it was to the other coconspirators who likewise

chose to rest upon their privilege not to testify.

50

Finally,

in response to an exception by Tandler's counsel, Judge

Herlands gave this supplemental instruction to the jury:

"The legal theory for this rule is immaterial so far as

you are concerned but the important and vital point for you as

jurors in this case to bear in mind is that a defendant has

the unqualified right not to take the stand, and you may not

in any manner draw any inference against the defendant because

he did not take the stand." We have held before that a

clear instruction of this character may cure any prejudice

resulting from an unfavorable comment, if such there was. See

United States v. Stromberg, supra, 268

F.2d at 271; United States v. Di Carlo, 64 F.2d 15

(2d Cir., 1933); United States v. De Vasto, 52 F.2d 26, 78

A.L.R. 336 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 284

U.S. 678, 52 S.Ct. 138, 76 L.Ed. 573 (1931). The

court's instruction was historically correct and, we find,

could not have been prejudicial, especially in the context of

this long trial. See United States v. Stromberg, supra, 268

F.2d at 271.

51

ALLEGED

PREJUDICIAL NEWSPAPER PUBLICITY

52

One

month after the opening of the trial, the New York press

reported the violent slaying of Albert Agueci, one of the

members of the so-called executive group. The victim, brother

of appellant Vito Agueci, was a fugitive from justice at the

time. Several of the jurors either read of the incident, heard

about it through radio or television, or heard it discussed in

the jury room. The news stories stated no reason for the death

of the victim, but merely indicated that another defendant had

been found dead some months before the trial, and that the

brother of the slain man, Vito, was on trial for violation of

the narcotics laws.

53

Immediately

upon learning of the publicity, Judge Herlands conducted an

extensive voir dire of the jury, questioning with great

care each juror who had heard of the incident. In response to

the questioning, the jurors assured the court that nothing

seen or heard would affect their deliberations or ability to

render a fair verdict. Throughout the voir dire

examination, Judge Herlands repeatedly made it clear that a

fair and impartial trial was essential, that it would be

necessary to excuse the jurors if their judgment were

prejudiced or unduly influenced by the publicity, and that the

case was to be decided only on the basis of evidence presented

in the courtroom. This last admonition was repeated in the

closing instructions to the jury.

54

We

hold that the nature of the publicity was such that, when

conjoined with the trial judge's cautionary instructions, no

prejudice resulted to defendant Vito Agueci or to his

codefendants.

55

"The

crux of the matter is whether the statements were so

prejudical as to require the trial judge, who has large

discretion in such matters, * * * to empanel a new jury."

United States v. Feldman, 299

F.2d 914, 917 (2d Cir., 1962). In those cases in

which newspaper publicity was deemed so prejudical as to

warrant reversal and an order for a new trial, the reports

contained information regarding such obviously inflammatory

and inadmissible matter as the prior criminal record of the

defendant, see, e. g., Marshall v. United States, 360

U.S. 310, 79 S.Ct. 1171, 3 L.Ed.2d 1250 (1959), or

clearly incriminatory out-of-court conduct, see, e. g., United

States v. Leviton, 193

F.2d 848 (2d Cir., 1951), cert. denied, 343

U.S. 946, 72 S.Ct. 860, 96 L.Ed. 1350 (1952).

Another matter of no small consequence which influenced the

disposition of the cases cited to us on behalf of the

appellants was the instrumental role of the Government in

bringing the adverse publicity to light. See United States v.

Leviton, supra; Delaney v. United States, 199

F.2d 107, 112-114 (1st Cir., 1952). Certainly these

categories are not all-inclusive, but the fact that the

information disclosed by the publicity here was not centered

upon any particular one of the appellants, did not refer to

prior illicit conduct, and did not emanate from the Government

but was a matter of general public knowledge, convinces us

that the appellants' right to a fair and impartial trial was

not impaired.

56

The

typical jury, in this age of mass-communications, is not

hermetically sealed from the events occurring all about them.

Of course, an effort must be made by the trial judge to

caution jurors against considering extra-judicial statements

pertinent to the guilt or innocence of the individuals upon

whom they sit in judgment. Where the cautionary instructions

are adequate, as they were here, and where the news reporting

was merely routine and hardly inflammatory, the trial judge

does not abuse his discretion by refusing to declare a

mistrial. See United States v. Stromberg, supra, 268

F.2d at 269-270; United States v. Postma, 242

F.2d 488, 495 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 354

U.S. 922, 77 S.Ct. 1380, 1 L.Ed. 2d 1436 (1957);

United States v. Allied Stevedoring Corp., 241

F.2d 925, 935 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 353

U.S. 984, 77 S.Ct. 1282, 1 L.Ed.2d 1143 (1957).

"Trial by newspaper may be unfortunate, but it is not new

and, unless the court accepts the standard judicial hypothesis

that cautioning instructions are effective, criminal trials in

the large metropolitan centers may well prove

impossible." United States v. Leviton, 193

F.2d at 857.

57

These

same considerations govern our disposition of the appellants'

contention that prejudice was caused by a news story relating

the fact that Judge Herlands, during the course of the trial,

revoked the bail of the defendants and remanded them to jail.

Of the three jurors who heard of this publicity, one had

merely been told that there was an article about the trial

judge in the newspaper, one had seen the headline but put the

article aside as soon as he realized that it related to the

case on trial, and one was an alternate juror who did not

participate in the jury's deliberations. There is obviously no

merit to this contention

58

OTHER

POINTS RAISED IN BEHALF OF ALL DEFENDANTS

59

Further

issues are raised which pertain to several or all of the

defendants. These can be disposed of within briefer compass.

60

The

great preponderance of testimony offered on behalf of the

Government was that of Matteo Palmeri and Salvatore Rinaldo,

two of the former members of the conspiracy. Their testimony

was corroborated in certain respects by immigrants who had

brought the valises and trunks to this country, by Government

agents, by two individuals living in Garfield, New Jersey, who

testified to the slip-up at the pier in early September of

1960, and by various documents, such as baggage manifests and

passenger lists. It is contended that the evidence against at

least one defendant, Luigi Lo Bue, rests solely upon the

testimony of coconspirator Matteo Palmeri. It is therefore

suggested that we ought to review the federal rule that the

uncorroborated testimony of an accomplice is sufficient to

convict. We hold, however, that the long-standing federal rule

does not require modification. See Caminetti v. United States,

242

U.S. 470, 495, 37 S.Ct. 192, 61 L.Ed. 442 (1917);

United States v. Moran, 151 F.2d 661 (2d Cir., 1945); United

States v. Schwartz, 150 F.2d 627 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 326

U.S. 757, 66 S.Ct. 97, 90 L.Ed. 454 (1945); United

States v. Quinn, 124 F.2d 378 (2d Cir., 1941); United States

v. Gallo, 123 F.2d 229 (2d Cir., 1941). Especially is this

principle appropriate in narcotics conspiracy cases, where

tangible evidence is often quickly sold or easily destroyed

and where conduct and contacts are always furtive. The

efficient administration of these vital federal laws could be

hampered beyond repair if testimony from the individuals who

know most about the illicit activity were insufficient to

sustain a conviction of their co-conspirators. We therefore

hold that the circumstance that the chief Government witnesses

were formerly members of the conspiracy is a matter which goes

merely to the weight of their testimony. Certainly the jury

should be carefully instructed as to the weight properly given

to "the uncorroborated testimony, inconsistent with his

earlier testimony in some respects, of an accomplice and

co-conspirator who had the strongest possible reasons to

become a Government witness." See United States v.

Persico, 305

F.2d 534, 536 (2d Cir., 1962). Judge Herlands'

instruction to the jury was more than adequate on this score.

He stated, "The testimony of Palmeri and Rinaldo, who are

accomplices by their own admission, must, as a matter of law,

be considered by you with close and searching scrutiny and

caution." See Bishop v. United States, 100 U.S.App. D.C.

88, 243

F.2d 32 (1957).

61

Appellants

contend also that the grand and petit juries were improperly

selected, and that a motion to dismiss the indictment and a

challenge to the array of the petit jury were improperly

disposed of by the trial court. Jury lists in the Southern

District of New York were drawn in this case from lists of

persons registered to vote at presidential elections in the

counties of New York, Bronx and Westchester. The contention

that this method of selection excludes a legally cognizable

group from jury service has been exhaustively treated and

completely repudiated in the considered opinion of Judge Bryan

in United States v. Greenberg, 200 F.Supp. 382 (S.D.N.Y.1961).

The qualifications for federal jury service set down in 28

U.S.C. § 18619

are strikingly similar to the requirements for voter

registration in the state of New York, see United States v.

Greenberg, supra, at 389; the cross-section of society

represented by those registration lists is so extensive as to

render frivolous the assertion of systematic exclusion. See

also Dow v. Carnegie-Illinois Steel Corp., 224

F.2d 414 (3d Cir., 1955), cert. denied, 350

U.S. 971, 76 S.Ct. 442, 100 L.Ed. 842 (1956);

United States v. Flynn, 216

F.2d 354 (2d Cir., 1954), cert. denied, 348

U.S. 909, 75 S.Ct. 295, 99 L.Ed. 713 (1955).

62

Finally,

the appellants as a group contend that the arrest of Rinaldo

and Palmeri on October 21, 1960 and the seizure of the

narcotics in the false-bottomed trunk, were brought about by

information obtained through a wiretap by Westchester County

police authorities and transmitted to agents of the federal

narcotics bureau. The evidence thus obtained is alleged to be

"fruit of the poisonous tree" which has been handed

on a "silver platter" from the state to the federal

authorities. This contention was asserted below, and Judge

Herlands quite properly held an extensive hearing to determine

whether the information secured by the state agents through

wiretapping had been transmitted to or used by the federal

agents in any fashion whatsoever. He concluded that federal

authorities "neither received nor used any wiretapping

evidence or information derived from the Westchester County

authorities or from any other local authorities" and that

"the record * * * overwhelmingly supports and sustains

the prosecution's contentions." We hold that his

conclusions are amply supported by the evidence and are not

clearly erroneous. Not only did the state officers sedulously

avoid communicating wiretap information to the federal

narcotics agents because of a consciousness that such evidence

would pollute a federal prosecution, but the record shows that

no evidence in any way pertinent to the case at hand was

turned up by the taps. Once the defendants offered evidence of

the existence of the wiretap, it was incumbent upon the

Government to prove that its evidence was not tainted by the

tap. United States v. Coplon, 185

F.2d 629, 636, 28 A.L.R.2d 1041 (2d Cir., 1950).

The Government clearly satisfied this burden; it was not

necessary to go further and disclose the precise source from

which its information did come.10

63

Moreover,

there is no merit to the appellants' contention that documents

containing prior statements by Government witness Rinaldo were

improperly used on redirect examination. They fall within the

rule of "verbal completeness," and were properly

used to place in context statements made on cross-examination.

See United States v. Lev, 276

F.2d 605, 608 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 363

U.S. 812, 80 S.Ct. 1248, 4 L.Ed. 2d 1153 (1960);

United States v. Apuzzo, 245

F.2d 416, 421-422 (2d Cir.) (en banc), cert.

denied, 355 U.S. 831, 78 S. Ct. 45, 2 L.Ed.2d 43 (1957); 7 Wigmore,

Evidence §§ 2094, 2115 (3d ed. 1940); McCormick, Evidence

132 (1954). Also without merit is the contention that the

trial judge's entry into the jury room — with

the consent of all counsel — to inform the

jurors that they might leave for lunch, was prejudicial and

constituted reversible error. It is undesirable that any

information not presented in the courtroom should reach a jury

after it has commenced its deliberations, except in those rare

instances where all concerned — counsel and the

judge — agree that a written communication to the

jurors is preferable to bringing them back into the courtroom.

But in this instance the judge decided, with everyone's

consent, to communicate personally the innocuous message to

the jurors. We believe that it would have been wiser had he

not, but that it would be "the merest pedantry" to

deem his conduct, under the circumstances present here, in any

manner prejudicial to the appellants. See United States v.

Compagna, 146 F.2d 524 (2d Cir., 1944), cert. denied, 324

U.S. 867, 65 S.Ct. 912, 89 L.Ed. 1422 (1945).

64

Having

disposed of those grounds urged for reversal which would

affect most or all of the appellants, we proceed to the

arguments raised by particular defendants in their own behalf.

65

COTTONE'S

CONSPIRACY CONVICTION

66

Filippo

Cottone was indicted and convicted under the conspiracy count

of the indictment; he was not charged with any substantive

violation of 21 U.S.C. § 174, which proscribes, among other

things, facilitating "the transportation, concealment, or

sale" of a narcotic drug knowing it to have been

imported. Cottone's sole connection with the conspiracy was

the assistance he rendered to Matteo Palmeri on September 6 or

7, 1960, when Palmeri was unable to use his bakery truck to

pick up the false-bottomed trunk waiting at Pier 84. The

Government's case against Cottone may be briefly summarized.

67

Albert

Agueci had told Palmeri that in the event his truck was ever

out of order he should contact Cottone. Palmeri did so,

informed Cottone that he needed his assistance to pick up a

trunk containing narcotics,11

and promised him $300 for his help. Cottone accompanied

Palmeri to the pier, Palmeri signed for the trunk, and both of

them loaded it into Cottone's station wagon. En route to

Palmeri's bakery, Cottone made the following comments:

"You never had any trouble before. How come you all

messed up this time? Like your truck is not in order, and you

can't find the passenger and all this trouble. I just can't

understand how you people operate. It is like a mess." At

the bakery, Cottone was introduced to Rinaldo as a man who was

"all right"; this was in response to Rinaldo's query

whether Mauro and Caruso knew that Palmeri was "taking

another man." Cottone participated in ripping open the

false-bottom of the trunk, which contained packages of heroin.

Cottone left the bakery with one of the blankets taken from

the trunk after all of the packages of heroin had supposedly

been extracted. When Palmeri later ascertained that there were

still three kilograms of heroin in the lining of the blanket,

he informed Cottone of this fact and retrieved the blanket.

Cottone received the $300 promised him for his services.

68

We

hold that the evidence clearly sustains Cottone's conviction

on the conspiracy count. From the testimony summarized above,

the jury could have readily inferred that Cottone knew that he

was assisting Palmeri in a transaction involving narcotics.

But it is urged that although Cottone may have known that the

substance imported was narcotics there was insufficient proof

from which a jury could conclude that he was aware that the

scope of the conspiracy was larger than his instant

participation and that there were more conspirators involved.

This argument is grounded primarily upon the fact that Cottone

was implicated in a single transaction involving only two

other individuals.

69

Several

cases decided by this court have held that proof of

participation in a single isolated narcotics transaction may

be insufficient to warrant a conviction for conspiracy. See

United States v. Aviles, 274

F.2d 179, 190 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 362

U.S. 974, 80 S.Ct. 1057, 4 L.Ed.2d 1009 (1960);

United States v. Stromberg, 268

F.2d 256, 267 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 361

U.S. 863, 80 S.Ct. 119, 4 L.Ed.2d 102 (1959);

United States v. Reina, 242

F.2d 302, 306 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 354

U.S. 913, 77 S. Ct. 1294, 1 L.Ed.2d 1427 (1957);

United States v. Koch, 113 F.2d 982 (2d Cir., 1940). But,

these cases also make it clear that the so-called

single-transaction rule is not an arbitrary rule which is to

be applied rigidly and without reason. It has been utilized to

exonerate a defendant only when there is no independent

evidence tending to prove that the defendant had some

knowledge of the broader conspiracy and when the single

transaction is not in itself one from which such knowledge

might be inferred. "A single act may be the foundation

for drawing the actor within the ambit of a conspiracy. * * *

But, since conviction of conspiracy requires an intent to

participate in the unlawful enterprise, the single act must be

such that one may reasonably infer from it such an

intent." United States v. Aviles, 274

F.2d at 189. We hold that there is independent

evidence from which Cottone's knowledge of the overall

conspiracy may be inferred, for he was introduced by Palmeri

to Rinaldo, was recommended to Palmeri by Albert Agueci for

assistance in these particular circumstances, and was present

when Rinaldo referred to Mauro and Caruso. Furthermore, his

conversation en route from the pier to the bakery revealed

that he was an old hand in the conspiratorial operation; so

too did his criticism of Palmeri for failing to locate the

passenger bringing in the trunk despite the fact that Palmeri

had never mentioned any such passenger to him.

70

We

need not rest on such particularized pieces of evidence, for

we further believe that a jury could reasonably infer from the

nature of this single transaction itself that Cottone had

knowledge of the conspiracy. He went to Pier 84 to assist in

procuring a trunk which he knew to contain narcotics; surely

he must have known that the trunk had been imported. He helped

to tear open the bottom of the trunk containing blankets in

which ten kilograms of narcotics had been secreted. He must

have known that such a large quantity of narcotics had not

reached their resting place, and the inference is again

inescapable that he knew that they would soon be distributed

to other illicit purchasers. It was under similar

circumstances that this Court found sufficient evidence to

support the conspiracy conviction in United States v. Bruno,

105 F. 2d 921 (2d Cir.), rev'd on other grounds, 308

U.S. 287, 60 S.Ct. 198, 84 L.Ed. 257 (1939).

71

We

have recently held that "From evidence of knowledge of

the conspiracy and a transaction with one of its members it

would be reasonable to infer intent to participate in it * *

*." United States v. Aviles, 274

F.2d at 190. We hold that there was ample evidence

to support Cottone's conviction on the conspiracy count.

72

PROSECUTOR'S

REMARKS IN SUMMATION

73

Cottone

argues that there is still another ground for reversing his

conviction. He charges that he was prejudiced by the improper

insinuation made in the prosecutor's summation that the lawyer

representing both Cottone and Scopellitti had been

instrumental in suborning their false testimony. Prior to the

trial, Mr. Lewis, who was Cottone's attorney, was requested by

the court also to represent the indigent defendant Scopellitti.

This he agreed to do. Before this, both Cottone and

Scopellitti had made pretrial statements. Their testimony at

trial, however, was different from those statements, and both

erected a similar defense.12

The Government prosecutor, in calling these facts to the

attention of the jury, stated:

74

"*

* * because that is what they told us before, wouldn't you

think or you might assume that they are going to give

basically the same story again? But then what happened? They

are both represented by Mr. Lewis. Both of them take the stand

and both of them have almost identical defenses. * * * What a

coincidence that is, too * * *."

75

It

is contended that the remark was so prejudicial to both

Cottone and Scopellitti that a mistrial should have been

ordered and that, on appeal, the defendants' convictions

should be reversed.

76

There

is no doubt that the prosecutor's thinly veiled accusation of

subornation of perjury on the part of Mr. Lewis was irregular

and improper. It would have been appropriate for the trial

judge to intercede sua sponte in order to caution the

jury to ignore the prosecutor's remarks. Such a remark by the

prosecutor might, in a case where the evidence against the

particular defendants was very tenuous, have caused enough

prejudice to be thrust upon the scales of justice, such that

they would be tipped onto the side of conviction; we would

then be constrained to reverse and order a new trial. But,

although we disapprove of the prosecuting attorney's remarks,

we feel that the evidence in support of Cottone's conspiracy

conviction was strong enough, and this isolated incident not

sufficiently prejudicial in the context of this long trial,

see United States v. Stromberg, supra, 268

F.2d at 271, to warrant a reversal.

77

In

reaching our conclusion, we further note that although Mr.

Lewis, after the entire summation was completed on December

22, 1961, approached the bench "on a point of personal

privilege" to ask that the prosecutor's attack be

referred to the bar association, there was at that time no

formal objection or suggestion that the portion of the

summation in question affected the rights of his clients. Nor

was a motion then made for a mistrial. Specifically, Mr. Lewis

objected to what he considered to be a slur upon his personal

integrity. Had a corrective charge been requested, it is

likely that one would have been given promptly, for the trial

judge was accommodating in that respect — as

witness his supplemental instruction regarding the right of

the defendants not to take the stand; but no such request was

made.

78

The

trial judge instructed all counsel on December 22 to submit in

memorandum form on the next trial date, December 26, any

motions, objections, or exceptions to the day's proceedings.

It is significant that it was not until the latter date that

counsel for Cottone and Scopellitti attempted to articulate

that the prosecutor's summation was prejudicial to his

clients. What must have been confusing to the trial judge,

however, was the fact that counsel's written objection

(Court's Exhibit XVIII) still appeared to be mainly concerned

with correcting the unwarranted attack on his professional

honor. Much the greater part of his objection was directed to

the effect which he believed the prosecutor's comments had

upon his standing at the bar. The first sentence of the

objection asked for a withdrawal of a juror and the

declaration of a mistrial "because of the scurrilous

attack made upon counsel"; counsel urged in the

alternative that if the mistrial be denied the case should be

reopened so that he might prove his many years of devotion to

and respect at the bar. He coupled this with a request that

the prosecutor's accusations be presented to a grand jury and

if untrue that they be called to the attention of Chief Judge

Lumbard for disciplinary action. He concluded his written

objection with the following statement: "This Court is

urged to take the necessary steps to inquire into the truth of

the prosecutor's remarks so that counsel's good name and his

standing as an honorable member of the bar be preserved."

It is significant that, despite the formalization of his

objection in the written memorandum of December 26, counsel

did not even then seek a corrective charge. The judge charged

the jury shortly after these objections were voiced. He could

with little difficulty have given a corrective charge had

counsel requested it and had he not distracted the judge by

demands for an investigation of his conduct by the bar

association, the grand jury, and the Chief Judge. We are

agreed that had a proper corrective charge been given, counsel

would have no cause to complain here. See United States v.

Stromberg, 268

F.2d 256, 271 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 361

U.S. 863, 80 S.Ct. 119, 4 L.Ed.2d 102 (1959). We

should not reward him for his failure to make this request.

79

In

any event, we choose to reject the assertion of error for the

reason that, while the prosecutor's remarks were improper, we

do not think they were so prejudicial as to require a new

trial. Cf. United States v. Greenberg, 268 F. 2d 120, 123-124

(2d Cir., 1959); United State v. De Fillo, 257

F.2d 835, 840 (2d Cir., 1958), cert. denied, 359

U.S. 915, 79 S.Ct. 591, 3 L.Ed.2d 577 (1959);

Williams v. United States, 265

F.2d 214, 216-217 (9th Cir., 1959).

80

Appellant

Scopellitti joins in urging that this incident was prejudicial

to him as well, especially, he says, in light of allegedly

insufficient evidence to support a finding that he had

knowledge that narcotics were contained in the trunk he

brought to this country on August 10, 1960. He admits, arguendo,

to knowledge of the smuggling operation and the false-bottomed

trunks, but contends that there is no proof that he knew the

substance smuggled was narcotics rather than some other

material. We cannot agree. Palmeri testified that Scopellitti

and Rinaldo broke open the bottom of the trunk Scopellitti

brought to this country and extracted ten packages of

narcotics; Scopellitti had earlier reassured his colleagues,

"don't worry. I know what it's all about." We hold

that the evidence was sufficient to support Scopellitti's

convictions for conspiracy and the substantive importation

violation of the narcotics law; and, for the reasons already

stated, that the prosecutor's attack upon the defendant's

counsel did not warrant reversal.

81

VALACHI'S

PURPORTED WITHDRAWAL FROM THE CONSPIRACY

82

Appellant